Transcription factor

In the field of molecular biology, a transcription factor (sometimes called a sequence-specific DNA binding factor) is a protein that binds to specific DNA sequences and thereby controls the transfer (or transcription) of genetic information from DNA to mRNA.[1][2] Transcription factors perform this function alone or with other proteins in a complex, by promoting (as an activator), or blocking (as a repressor) the recruitment of RNA polymerase (the enzyme that performs the transcription of genetic information from DNA to RNA) to specific genes.[3][4][5]

A defining feature of transcription factors is that they contain one or more DNA-binding domains (DBDs), which attach to specific sequences of DNA adjacent to the genes that they regulate.[6][7] Additional proteins such as coactivators, chromatin remodelers, histone acetylases, deacetylases, kinases, and methylases, while also playing crucial roles in gene regulation, lack DNA-binding domains, and therefore are not classified as transcription factors.[8]

| Transcription factor glossary |

|---|

| • transcription – copying of DNA by RNA polymerase into messenger RNA |

| • factor – a substance, such as a protein, that contributes to the cause of a specific biochemical reaction or bodily process |

| • transcriptional regulation – controlling the rate of gene transcription for example by helping or hindering RNA polymerase binding to DNA |

| • upregulation, activation, or promotion – increase the rate of gene transcription |

| • downregulation, repression, or suppression – decrease the rate of gene transcription |

| • coactivator – a protein that works with transcription factors to increase the rate of gene transcription |

| • corepressor – a protein that works with transcription factors to decrease the rate of gene transcription |

| edit |

Contents |

Conservation in different organisms

Transcription factors are essential for the regulation of gene expression and are, as a consequence, found in all living organisms. The number of transcription factors found within an organism increases with genome size, and larger genomes tend to have more transcription factors per gene.[9]

There are approximately 2600 proteins in the human genome that contain DNA-binding domains, and most of these are presumed to function as transcription factors.[10] Therefore, approximately 10% of genes in the genome code for transcription factors, which makes this family the single largest family of human proteins. Furthermore, genes are often flanked by several binding sites for distinct transcription factors, and efficient expression of each of these genes requires the cooperative action of several different transcription factors (see, for example, hepatocyte nuclear factors). Hence, the combinatorial use of a subset of the approximately 2000 human transcription factors easily accounts for the unique regulation of each gene in the human genome during development.[8]

Mechanism

Transcription factors bind to either enhancer or promoter regions of DNA adjacent to the genes that they regulate. Depending on the transcription factor, the transcription of the adjacent gene is either up- or down-regulated. Transcription factors use a variety of mechanisms for the regulation of gene expression.[11] These mechanisms include:

- stabilize or block the binding of RNA polymerase to DNA

- catalyze the acetylation or deacetylation of histone proteins. The transcription factor can either do this directly or recruit other proteins with this catalytic activity. More specially many transcription factors use one or the other of two opposing mechanisms to regulate transcription:[12]

- histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity – acetylates histone proteins, which weakens the association of DNA with histones, which make the DNA more accessible to transcription and thereby upregulate transcription

- histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity – deacetylates histone proteins, which strengthens the association of DNA with histones, which make the DNA less accessible to transcription and thereby down regulate transcription

- recruit coactivator or corepressor proteins to the transcription factor DNA complex[13]

Function

Transcription factors are one of the groups of proteins that read and interpret the genetic "blueprint" in the DNA. They bind DNA and help initiate a program of increased or decreased gene transcription. As such, they are vital for many important cellular processes. Below are some of the important functions and biological roles transcription factors are involved in:

Basal transcription regulation

In eukaryotes, an important class of transcription factors called general transcription factors (GTFs) are necessary for transcription to occur.[14][15][16] Many of these GTFs don't actually bind DNA but are part of the large transcription preinitiation complex that interacts with RNA polymerase directly. The most common GTFs are TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIID (see also TATA binding protein), TFIIE, TFIIF, and TFIIH.[17] The preinitiation complex binds to promoter regions of DNA upstream to the gene that they regulate.

Differential enhancement of transcription

Other transcription factors differentially regulate the expression of various genes by binding to enhancer regions of DNA adjacent to regulated genes. These transcription factors are critical to making sure that genes are expressed in the right cell at the right time and in the right amount depending on the changing requirements of the organism.

Development

Many transcription factors in multicellular organisms are involved in development.[18] Responding to cues (stimuli), these transcription factors turn on/off the transcription of the appropriate genes, which, in turn, allows for changes in cell morphology or activities needed for cell fate determination and cellular differentiation. The Hox transcription factor family, for example, is important for proper body pattern formation in organisms as diverse as fruit flies to humans.[19][20] Another example is the transcription factor encoded by the Sex-determining Region Y (SRY) gene, which plays a major role in determining gender in humans.[21]

Response to intercellular signals

Cells can communicate with each other by releasing molecules that produce signaling cascades within another receptive cell. If the signal requires upregulation or downregulation of genes in the recipient cell, often transcription factors will be downstream in the signaling cascade.[22] Estrogen signaling is an example of a fairly short signaling cascade that involves the estrogen receptor transcription factor: estrogen is secreted by tissues such as the ovaries and placenta, crosses the cell membrane of the recipient cell, and is bound by the estrogen receptor in the cell's cytoplasm. The estrogen receptor then goes to the cell's nucleus and binds to its DNA-binding sites, changing the transcriptional regulation of the associated genes.[23]

Response to environment

Not only do transcription factors act downstream of signaling cascades related to biological stimuli but they can also be downstream of signaling cascades involved in environmental stimuli. Examples include heat shock factor (HSF), which upregulates genes necessary for survival at higher temperatures,[24] hypoxia inducible factor (HIF), which upregulates genes necessary for cell survival in low-oxygen environments,[25] and sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP), which helps maintain proper lipid levels in the cell.[26]

Cell cycle control

Many transcription factors, especially some that are oncogenes or tumor suppressors, help regulate the cell cycle and as such determine how large a cell will get and when it can divide into two daughter cells.[27][28] One example is the Myc oncogene, which has important roles in cell growth and apoptosis.[29]

Regulation

It is common in biology for important processes to have multiple layers of regulation and control. This is also true with transcription factors: not only do transcription factors control the rates of transcription to regulate the amounts of gene products (RNA and protein) available to the cell, but transcription factors themselves are regulated (often by other transcription factors). Below is a brief synopsis of some of the ways that the activity of transcription factors can be regulated:

Synthesis

Transcription factors (like all proteins) are transcribed from a gene on a chromosome into RNA, and then the RNA is translated into protein. Any of these steps can be regulated to affect the production (and thus activity) of a transcription factor. One interesting implication of this is that transcription factors can regulate themselves. For example, in a negative feedback loop, the transcription factor acts as its own repressor: if the transcription factor protein binds the DNA of its own gene, it will down-regulate the production of more of itself. This is one mechanism to maintain low levels of a transcription factor in a cell.

Nuclear localization

In eukaryotes, transcription factors (like most proteins) are transcribed in the nucleus but are then translated in the cell's cytoplasm. Many proteins that are active in the nucleus contain nuclear localization signals that direct them to the nucleus. But, for many transcription factors, this is a key point in their regulation.[30] Important classes of transcription factors such as some nuclear receptors must first bind a ligand while in the cytoplasm before they can relocate to the nucleus.[30]

Activation

Transcription factors may be activated (or deactivated) through their signal-sensing domain by a number of mechanisms including:

- ligand binding – Not only is ligand binding able to influence where a transcription factor is located within a cell but ligand binding can also affect whether the transcription factor is in an active state and capable of binding DNA or other cofactors (see for example nuclear receptors).

- phosphorylation[31][32] – Many transcription factors such as STAT proteins must be phosphorylated before they can bind DNA.

- interaction with other transcription factors (e.g., homo- or hetero-dimerization) or coregulatory proteins

Accessibility of DNA-binding site

In eukaryotes, genes that are not being actively transcribed are often located in heterochromatin. Heterochromatin are regions of chromosomes that are heavily compacted by tightly bundling the DNA onto histones and then organizing the histones into compact chromatin fibers. DNA within heterochromatin is inaccessible to many transcription factors. For the transcription factor to bind to its DNA-binding site, the heterochromatin must first be converted to euchromatin, usually via histone modifications. A transcription factor's DNA-binding site may also be inaccessible if the site is already occupied by another transcription factor. Pairs of transcription factors can play antagonistic roles (activator versus repressor) in the regulation of the same gene.

Availability of other cofactors/transcription factors

Most transcription factors do not work alone. Often for gene transcription to occur, a number of transcription factors must bind to DNA regulatory sequences. This collection of transcription factors in turn recruit intermediary proteins such as cofactors that allow efficient recruitment of the preinitiation complex and RNA polymerase. Thus, for a single transcription factor to initiate transcription, all of these other proteins must also be present, and the transcription factor must be in a state where it can bind to them if necessary.

Structure

Transcription factors are modular in structure and contain the following domains:[1]

- DNA-binding domain (DBD), which attach to specific sequences of DNA (enhancer or promoter sequences) adjacent to regulated genes. DNA sequences that bind transcription factors are often referred to as response elements.

- Trans-activating domain (TAD), which contain binding sites for other proteins such as transcription coregulators. These binding sites are frequently referred to as activation functions (AFs).[33]

- An optional signal sensing domain (SSD) (e.g., a ligand binding domain), which senses external signals and in response transmit these signals to the rest of the transcription complex, resulting in up or down regulation of gene expression. Also, the DBD and signal-sensing domains may reside on separate proteins that associate within the transcription complex to regulate gene expression.

Trans-activating domain

Trans-activating domains (TADs) are named after their amino acid composition. These amino acids are either essential for the activity or simply the most abundant in the TAD. Transactivation by the Gal4 transcription factor is mediated by acidic amino acids whereas hydrophobic residues in Gcn4 play a similar role. Hence the TADs in Gal4 and Gcn4 are referred to as acidic or hydrophobic activation domains respectively.[34]

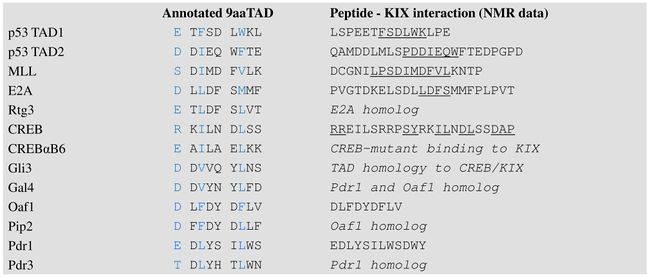

Nine-amino-acid transactivation domain (9aaTAD) defines a novel domain common to a large superfamily of eukaryotic transcription factors represented by Gal4, Oaf1, Leu3, Rtg3, Pho4, Gln3, Gcn4 in yeast and by p53, NFAT, NF-κB and VP16 in mammals.[35] Prediction for 9aa TADs (for both acidic and hydrophilic transactivation domains) is available online from ExPASy [36] and EMBnet Spain [37]

9aaTAD transcription factors p53, VP16, MLL, E2A, HSF1, NF-IL6, NFAT1 and NF-κB interact directly with the general coactivators TAF9 and CBP/p300.[38] p53 9aaTADs interact with TAF9, GCN5 and with multiple domains of CBP/p300 (KIX, TAZ1,TAZ2 and IBiD).[39]

KIX domain of general coactivators Med15(Gal11) interacts with 9aaTAD transcription factors Gal4, Pdr1, Oaf1, Gcn4, VP16, Pho4, Msn2, Ino2 and P201.[40] Interactions of Gal4, Pdr1 and Gcn4 with Taf9 were reported. [41] 9aaTAD is a common transactivation domain recruits multiple general coactivators TAF9, MED15, CBP/p300 and GCN5.[42]

DNA-binding domain

The portion (domain) of the transcription factor that binds DNA is called its DNA-binding domain. Below is a partial list of some of the major families of DNA-binding domains/transcription factors:

| Family | InterPro | Pfam | SCOP |

|---|---|---|---|

| basic-helix-loop-helix[43] | IPR001092 | Pfam PF00010 | SCOP 47460 |

| basic-leucine zipper (bZIP)[44] | IPR004827 | Pfam PF00170 | SCOP 57959 |

| C-terminal effector domain of the bipartite response regulators | IPR001789 | Pfam PF00072 | SCOP 46894 |

| GCC box | SCOP 54175 | ||

| helix-turn-helix[45] | |||

| homeodomain proteins - bind to homeobox DNA sequences, which in turn encode other transcription factors. Homeodomain proteins play critical roles in the regulation of development.[46] | IPR009057 | Pfam PF00046 | SCOP 46689 |

| lambda repressor-like | IPR010982 | SCOP 47413 | |

| srf-like (serum response factor) | IPR002100 | Pfam PF00319 | SCOP 55455 |

| paired box[47] | |||

| winged helix | IPR013196 | Pfam PF08279 | SCOP 46785 |

| zinc fingers[48] | |||

| * multi-domain Cys2His2 zinc fingers[49] | IPR007087 | Pfam PF00096 | SCOP 57667 |

| * Zn2/Cys6 | SCOP 57701 | ||

| * Zn2/Cys8 nuclear receptor zinc finger | IPR001628 | Pfam PF00105 | SCOP 57716 |

Response elements

The DNA sequence that a transcription factor binds to is called a transcription factor-binding site or response element.[50]

Transcription factors interact with their binding sites using a combination of electrostatic (of which hydrogen bonds are a special case) and Van der Waals forces. Due to the nature of these chemical interactions, most transcription factors bind DNA in a sequence specific manner. However, not all bases in the transcription factor-binding site may actually interact with the transcription factor. In addition, some of these interactions may be weaker than others. Thus, transcription factors do not bind just one sequence but are capable of binding a subset of closely related sequences, each with a different strength of interaction.

For example, although the consensus binding site for the TATA-binding protein (TBP) is TATAAAA, the TBP transcription factor can also bind similar sequences such as TATATAT or TATATAA.

Because transcription factors can bind a set of related sequences and these sequences tend to be short, potential transcription factor binding sites can occur by chance if the DNA sequence is long enough. It is unlikely, however, that a transcription factor binds all compatible sequences in the genome of the cell. Other constraints, such as DNA accessibility in the cell or availability of cofactors may also help dictate where a transcription factor will actually bind. Thus, given the genome sequence it is still difficult to predict where a transcription factor will actually bind in a living cell.

Additional recognition specificity, however, may be obtained through the use of more than one DNA-binding domain (for example tandem DBDs in the same transcription factor or through dimerization of two transcription factors) that bind to two or more adjacent sequences of DNA.

Clinical significance

Transcription factors are of clinical significance for at least two reasons: (1) mutations can be associated with specific diseases, and (2) they can be targets of medications.

Disorders

Due to their important roles in development, intercellular signaling, and cell cycle, some human diseases have been associated with mutations in transcription factors.[51]

Cancer Many transcription factors are either tumor suppressors or oncogenes, and, thus, mutations or aberrant regulation of them is associated with cancer. Three groups of transcription factors are known to be important in human cancer : 1) the NF-kappaB and AP-1 families, 2) the STAT family and 3) the steroids receptors.[52].

Below are a few of the more well-studied examples:

| Condition | Description | Locus |

|---|---|---|

| Rett syndrome | Mutations in the MECP2 transcription factor are associated with Rett syndrome, a neurodevelopmental disorder.[53][54] | Xq28 |

| Diabetes | A rare form of diabetes called MODY (Maturity onset diabetes of the young) can be caused by mutations in hepatocyte nuclear factors (HNFs)[55] or insulin promoter factor-1 (IPF1/Pdx1).[56] | multiple |

| Developmental verbal dyspraxia | Mutations in the FOXP2 transcription factor are associated with developmental verbal dyspraxia, a disease in which individuals are unable to produce the finely coordinated movements required for speech.[57] | 7q31 |

| Autoimmune diseases | Mutations in the FOXP3 transcription factor cause a rare form of autoimmune disease called IPEX.[58] | Xp11.23-q13.3 |

| Li-Fraumeni syndrome | Caused by mutations in the tumor suppressor p53.[59] | 17p13.1 |

| breast cancer | The STAT family is relevant to breast cancer.[60] | multiple |

| multiple cancers | The HOX family are involved in a variety of cancers.[61] | multiple |

Potential drug targets

Approximately 10% of currently prescribed drugs directly target the nuclear receptor class of transcription factors.[62] Examples include tamoxifen and bicalutamide for the treatment of breast and prostate cancer, respectively, and various types of anti-inflammatory and anabolic steroids.[63] In addition, transcription factors are often indirectly modulated by drugs through signaling cascades. It might be possible to directly target other less-explored transcription factors such as NF-κB with drugs.[64][65][66][67] Transcription factors outside the nuclear receptor family are thought to be more difficult to target with small molecule therapeutics since it is not clear that they are "drugable" but progress has been made on the notch pathway.[68]

Analysis

There are different technologies available to analyze transcription factors. On the genomic level, DNA-sequencing[69] and database research are commonly used. The protein version of the transcription factor is detectable by using specific antibodies. The sample is detected on a western blot. By using electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA),[70] the activation profile of transcription factors can be detected. A multiplex approach for activation profiling is a TF chip system where several of different transcription factors can be detected in parallel. This technology is based on DNA microarrays, providing the specific DNA-binding sequence for the transcription factor protein on the array surface.[71]

Classes

As described in more detail below, transcription factors may be classified by their (1) mechanism of action, (2) regulatory function, or (3) sequence homology (and hence structural similarity) in their DNA-binding domains.

Mechanistic

There are three mechanistic classes of transcription factors:

- General transcription factors are involved in the formation of a preinitiation complex. The most common are abbreviated as TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIID, TFIIE, TFIIF, and TFIIH. They are ubiquitous and interact with the core promoter region surrounding the transcription start site(s) of all class II genes.[72]

- Upstream transcription factors are proteins that bind somewhere upstream of the initiation site to stimulate or repress transcription. These are roughly synonymous with specific transcription factors, because they vary considerably depending on what recognition sequences are present in the proximity of the gene. [73]

| Examples of specific transcription factors[73] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Structural type | Recognition sequence | Binds as |

| SP1 | Zinc finger | 5'-GGGCGG-3' | Monomer |

| AP-1 | Basic zipper | 5'-TGA(G/C)TCA-3' | Dimer |

| C/EBP | Basic zipper | 5'-ATTGCGCAAT-3' | Dimer |

| Heat shock factor | Basic zipper | 5'-XGAAX-3' | Trimer |

| ATF/CREB | Basic zipper | 5'-TGACGTCA-3' | Dimer |

| c-Myc | Basic-helix-loop-helix | 5'-CACGTG-3' | Dimer |

| Oct-1 | Helix-turn-helix | 5'-ATGCAAAT-3' | Monomer |

| NF-1 | Novel | 5'-TTGGCXXXXXGCCAA-3' | Dimer |

Functional

Transcription factors have been classified according to their regulatory function:[8]

- I. constitutively-active – present in all cells at all times – general transcription factors, Sp1, NF1, CCAAT

- II. conditionally-active – requires activation

- II.A developmental (cell specific) – expression is tightly controlled, but, once expressed, require no additional activation – GATA, HNF, PIT-1, MyoD, Myf5, Hox, Winged Helix

- II.B signal-dependent – requires external signal for activation

- II.B.1 extracellular ligand (endocrine or paracrine)-dependent – nuclear receptors

- II.B.2 intracellular ligand (autocrine)-dependent - activated by small intracellular molecules – SREBP, p53, orphan nuclear receptors

- II.B.3 cell membrane receptor-dependent – second messenger signaling cascades resulting in the phosphorylation of the transcription factor

- II.B.3.a resident nuclear factors – reside in the nucleus regardless of activation state – CREB, AP-1, Mef2

- II.B.3.b latent cytoplasmic factors – inactive form reside in the cytoplasm, but, when activated, are translocated into the nucleus – STAT, R-SMAD, NF-κB, Notch, TUBBY, NFAT

Structural

Transcription factors are often classified based on the sequence similarity and hence the tertiary structure of their DNA-binding domains:[74][75][76]

- 1 Superclass: Basic Domains (Basic-helix-loop-helix)

- 1.1 Class: Leucine zipper factors (bZIP)

- 1.1.1 Family: AP-1(-like) components; includes (c-Fos/c-Jun)

- 1.1.2 Family: CREB

- 1.1.3 Family: C/EBP-like factors

- 1.1.4 Family: bZIP / PAR

- 1.1.5 Family: Plant G-box binding factors

- 1.1.6 Family: ZIP only

- 1.2 Class: Helix-loop-helix factors (bHLH)

- 1.2.1 Family: Ubiquitous (class A) factors

- 1.2.2 Family: Myogenic transcription factors (MyoD)

- 1.2.3 Family: Achaete-Scute

- 1.2.4 Family: Tal/Twist/Atonal/Hen

- 1.3 Class: Helix-loop-helix / leucine zipper factors (bHLH-ZIP)

- 1.3.1 Family: Ubiquitous bHLH-ZIP factors; includes USF (USF1, USF2); SREBP (SREBP)

- 1.3.2 Family: Cell-cycle controlling factors; includes c-Myc

- 1.4 Class: NF-1

- 1.4.1 Family: NF-1 (A, B, C, X)

- 1.5 Class: RF-X

- 1.5.1 Family: RF-X (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, ANK)

- 1.6 Class: bHSH

- 1.1 Class: Leucine zipper factors (bZIP)

- 2 Superclass: Zinc-coordinating DNA-binding domains

- 2.1 Class: Cys4 zinc finger of nuclear receptor type

- 2.1.1 Family: Steroid hormone receptors

- 2.1.2 Family: Thyroid hormone receptor-like factors

- 2.2 Class: diverse Cys4 zinc fingers

- 2.2.1 Family: GATA-Factors

- 2.3 Class: Cys2His2 zinc finger domain

- 2.3.1 Family: Ubiquitous factors, includes TFIIIA, Sp1

- 2.3.2 Family: Developmental / cell cycle regulators; includes Krüppel

- 2.3.4 Family: Large factors with NF-6B-like binding properties

- 2.4 Class: Cys6 cysteine-zinc cluster

- 2.5 Class: Zinc fingers of alternating composition

- 2.1 Class: Cys4 zinc finger of nuclear receptor type

- 3 Superclass: Helix-turn-helix

- 3.1 Class: Homeo domain

- 3.1.1 Family: Homeo domain only; includes Ubx

- 3.1.2 Family: POU domain factors; includes Oct

- 3.1.3 Family: Homeo domain with LIM region

- 3.1.4 Family: homeo domain plus zinc finger motifs

- 3.2 Class: Paired box

- 3.2.1 Family: Paired plus homeo domain

- 3.2.2 Family: Paired domain only

- 3.3 Class: Fork head / winged helix

- 3.3.1 Family: Developmental regulators; includes forkhead

- 3.3.2 Family: Tissue-specific regulators

- 3.3.3 Family: Cell-cycle controlling factors

- 3.3.0 Family: Other regulators

- 3.4 Class: Heat Shock Factors

- 3.4.1 Family: HSF

- 3.5 Class: Tryptophan clusters

- 3.5.1 Family: Myb

- 3.5.2 Family: Ets-type

- 3.5.3 Family: Interferon regulatory factors

- 3.6 Class: TEA ( transcriptional enhancer factor) domain

- 3.6.1 Family: TEA (TEAD1, TEAD2, TEAD3, TEAD4)

- 3.1 Class: Homeo domain

- 4 Superclass: beta-Scaffold Factors with Minor Groove Contacts

- 4.1 Class: RHR (Rel homology region)

- 4.1.1 Family: Rel/ankyrin; NF-kappaB

- 4.1.2 Family: ankyrin only

- 4.1.3 Family: NFAT (Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells) (NFATC1, NFATC2, NFATC3)

- 4.2 Class: STAT

- 4.2.1 Family: STAT

- 4.3 Class: p53

- 4.3.1 Family: p53

- 4.4 Class: MADS box

- 4.4.1 Family: Regulators of differentiation; includes (Mef2)

- 4.4.2 Family: Responders to external signals, SRF (serum response factor) (SRF)

- 4.4.1 Family: Regulators of differentiation; includes (Mef2)

- 4.5 Class: beta-Barrel alpha-helix transcription factors

- 4.6 Class: TATA binding proteins

- 4.6.1 Family: TBP

- 4.7.1 Family: SOX genes, SRY

- 4.7.2 Family: TCF-1 (TCF1)

- 4.7.3 Family: HMG2-related, SSRP1

- 4.7.5 Family: MATA

- 4.8 Class: Heteromeric CCAAT factors

- 4.8.1 Family: Heteromeric CCAAT factors

- 4.9 Class: Grainyhead

- 4.9.1 Family: Grainyhead

- 4.10 Class: Cold-shock domain factors

- 4.10.1 Family: csd

- 4.11 Class: Runt

- 4.11.1 Family: Runt

- 4.1 Class: RHR (Rel homology region)

- 0 Superclass: Other Transcription Factors

- 0.1 Class: Copper fist proteins

- 0.2 Class: HMGI(Y) (HMGA1)

- 0.2.1 Family: HMGI(Y)

- 0.3 Class: Pocket domain

- 0.4 Class: E1A-like factors

- 0.5 Class: AP2/EREBP-related factors

- 0.5.1 Family: AP2

- 0.5.2 Family: EREBP

- 0.5.3 Superfamily: AP2/B3

- 0.5.3.1 Family: ARF

- 0.5.3.2 Family: ABI

- 0.5.3.3 Family: RAV

See also

- DNA-binding protein

- Inhibitor of DNA-binding protein

- Nuclear receptor, a class of ligand activated transcription factors

- Phylogenetic footprinting

- Cdx protein family

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Latchman DS (1997). "Transcription factors: an overview". Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 29 (12): 1305–12. doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(97)00085-X. PMID 9570129.

- ↑ Karin M (1990). "Too many transcription factors: positive and negative interactions". New Biol. 2 (2): 126–31. PMID 2128034.

- ↑ Roeder RG (1996). "The role of general initiation factors in transcription by RNA polymerase II". Trends Biochem. Sci. 21 (9): 327–35. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(96)10050-5. PMID 8870495.

- ↑ Nikolov DB, Burley SK (1997). "RNA polymerase II transcription initiation: a structural view". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 (1): 15–22. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.1.15. PMID 8990153.

- ↑ Lee TI, Young RA (2000). "Transcription of eukaryotic protein-coding genes". Annu. Rev. Genet. 34: 77–137. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.77. PMID 11092823.

- ↑ Mitchell PJ, Tjian R (1989). "Transcriptional regulation in mammalian cells by sequence-specific DNA binding proteins". Science 245 (4916): 371–8. doi:10.1126/science.2667136. PMID 2667136.

- ↑ Ptashne M, Gann A (1997). "Transcriptional activation by recruitment". Nature 386 (6625): 569–77. doi:10.1038/386569a0. PMID 9121580.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Brivanlou AH, Darnell JE (2002). "Signal transduction and the control of gene expression". Science 295 (5556): 813–8. doi:10.1126/science.1066355. PMID 11823631.

- ↑ van Nimwegen E (2003). "Scaling laws in the functional content of genomes". Trends Genet. 19 (9): 479–84. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00203-8. PMID 12957540.

- ↑ Babu MM, Luscombe NM, Aravind L, Gerstein M, Teichmann SA (2004). "Structure and evolution of transcriptional regulatory networks". Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14 (3): 283–91. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2004.05.004. PMID 15193307.

- ↑ Gill G (2001). "Regulation of the initiation of eukaryotic transcription". Essays Biochem. 37: 33–43. PMID 11758455.

- ↑ Narlikar GJ, Fan HY, Kingston RE (February 2002). "Cooperation between complexes that regulate chromatin structure and transcription". Cell 108 (4): 475–87. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00654-2. PMID 11909519.

- ↑ Xu L, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG (April 1999). "Coactivator and corepressor complexes in nuclear receptor function". Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 9 (2): 140–7. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80021-5. PMID 10322133.

- ↑ Robert O. J. Weinzierl (1999). Mechanisms of Gene Expression: Structure, Function and Evolution of the Basal Transcriptional Machinery. World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 1-86094-126-5.

- ↑ Reese JC (April 2003). "Basal transcription factors". Current opinion in genetics & development 13 (2): 114–8. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(03)00013-3. PMID 12672487.

- ↑ Shilatifard A, Conaway RC, Conaway JW (2003). "The RNA polymerase II elongation complex". Annual review of biochemistry 72: 693–715. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161551. PMID 12676794.

- ↑ Thomas MC, Chiang CM (2006). "The general transcription machinery and general cofactors". Critical reviews in biochemistry and molecular biology 41 (3): 105–78. doi:10.1080/10409230600648736. PMID 16858867.

- ↑ Lobe CG (1992). "Transcription factors and mammalian development". Current topics in developmental biology 27: 351–83. doi:10.1016/S0070-2153(08)60539-6. PMID 1424766.

- ↑ Lemons D, McGinnis W (September 2006). "Genomic evolution of Hox gene clusters". Science (New York, N.Y.) 313 (5795): 1918–22. doi:10.1126/science.1132040. PMID 17008523.

- ↑ Moens CB, Selleri L (March 2006). "Hox cofactors in vertebrate development". Developmental biology 291 (2): 193–206. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.10.032. PMID 16515781.

- ↑ Ottolenghi C, Uda M, Crisponi L, Omari S, Cao A, Forabosco A, Schlessinger D (January 2007). "Determination and stability of sex". BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology 29 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1002/bies.20515. PMID 17187356.

- ↑ Pawson T (1993). "Signal transduction--a conserved pathway from the membrane to the nucleus". Developmental genetics 14 (5): 333–8. doi:10.1002/dvg.1020140502. PMID 8293575.

- ↑ Osborne CK, Schiff R, Fuqua SA, Shou J (December 2001). "Estrogen receptor: current understanding of its activation and modulation". Clin. Cancer Res. 7 (12 Suppl): 4338s–4342s; discussion 4411s–4412s. PMID 11916222.

- ↑ Shamovsky I, Nudler E (March 2008). "New insights into the mechanism of heat shock response activation". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65 (6): 855–61. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-7458-y. PMID 18239856.

- ↑ Benizri E, Ginouvès A, Berra E (April 2008). "The magic of the hypoxia-signaling cascade". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65 (7-8): 1133–49. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-7472-0. PMID 18202826.

- ↑ Weber LW, Boll M, Stampfl A (November 2004). "Maintaining cholesterol homeostasis: sterol regulatory element-binding proteins". World J. Gastroenterol. 10 (21): 3081–7. PMID 15457548. http://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/10/3081.asp.

- ↑ Wheaton K, Atadja P, Riabowol K (1996). "Regulation of transcription factor activity during cellular aging". Biochem. Cell Biol. 74 (4): 523–34. doi:10.1139/o96-056. PMID 8960358.

- ↑ Meyyappan M, Atadja PW, Riabowol KT (1996). "Regulation of gene expression and transcription factor binding activity during cellular aging". Biol. Signals 5 (3): 130–8. doi:10.1159/000109183. PMID 8864058.

- ↑ Evan G, Harrington E, Fanidi A, Land H, Amati B, Bennett M (August 1994). "Integrated control of cell proliferation and cell death by the c-myc oncogene". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 345 (1313): 269–75. doi:10.1098/rstb.1994.0105. PMID 7846125.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Whiteside ST, Goodbourn S (April 1993). "Signal transduction and nuclear targeting: regulation of transcription factor activity by subcellular localisation". Journal of cell science 104 ( Pt 4): 949–55. PMID 8314906. http://jcs.biologists.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=8314906.

- ↑ Bohmann D (November 1990). "Transcription factor phosphorylation: a link between signal transduction and the regulation of gene expression". Cancer cells (Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. : 1989) 2 (11): 337–44. PMID 2149275.

- ↑ Weigel NL, Moore NL (2007). "Steroid Receptor Phosphorylation: A Key Modulator of Multiple Receptor Functions". Molecular Endocrinology 21 (10): 2311. doi:10.1210/me.2007-0101. PMID 17536004.

- ↑ Wärnmark A, Treuter E, Wright AP, Gustafsson J-Å (2003). "Activation functions 1 and 2 of nuclear receptors: molecular strategies for transcriptional activation". Mol. Endocrinol. 17 (10): 1901–9. doi:10.1210/me.2002-0384. PMID 12893880.

- ↑ Ma J, Ptashne M (October 1987). "A new class of yeast transcriptional activators". Cell 51 (1): 113–9. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90015-8. PMID 3115591.Sadowski I, Ma J, Triezenberg S, Ptashne M (October 1988). "GAL4-VP16 is an unusually potent transcriptional activator". Nature 335 (6190): 563–4. doi:10.1038/335563a0. PMID 3047590.Sullivan SM, Horn PJ, Olson VA, Koop AH, Niu W, Ebright RH, Triezenberg SJ (October 1998). "Mutational analysis of a transcriptional activation region of the VP16 protein of herpes simplex virus". Nucleic Acids Res. 26 (19): 4487–96. doi:10.1093/nar/26.19.4487. PMID 9742254.Gill G, Ptashne M (October 1987). "Mutants of GAL4 protein altered in an activation function". Cell 51 (1): 121–6. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90016-X. PMID 3115592.Hope IA, Mahadevan S, Struhl K (June 1988). "Structural and functional characterization of the short acidic transcriptional activation region of yeast GCN4 protein". Nature 333 (6174): 635–40. doi:10.1038/333635a0. PMID 3287180.Hope IA, Struhl K (September 1986). "Functional dissection of a eukaryotic transcriptional activator protein, GCN4 of yeast". Cell 46 (6): 885–94. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(86)90070-X. PMID 3530496.Drysdale CM, Dueñas E, Jackson BM, Reusser U, Braus GH, Hinnebusch AG (March 1995). "The transcriptional activator GCN4 contains multiple activation domains that are critically dependent on hydrophobic amino acids". Mol. Cell. Biol. 15 (3): 1220–33. PMID 7862116. PMC 230345. http://mcb.asm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7862116.Regier JL, Shen F, Triezenberg SJ (February 1993). "Pattern of aromatic and hydrophobic amino acids critical for one of two subdomains of the VP16 transcriptional activator". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90 (3): 883–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.3.883. PMID 8381535.

- ↑ {{cite journal | author = Piskacek S, Gregor M, Nemethova M, Grabner M, Kovarik P, Piskacek M | title = Nine-amino-acid transactivation domain: establishment and prediction utilities | journal = Genomics | volume = 89 | issue = 6 | pages = 756–68 | year = 2007 | month = June | pmid = 17467953 | doi = 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.02.003 ; Martin Piskacek, Nature Precedings http://precedings.nature.com/documents/3488/version/2 (2009); Martin Piskacek, Nature Precedings http://precedings.nature.com/documents/3939/version/1 (2009); Martin Piskacek, Nature Precedings (2009) http://precedings.nature.com/documents/3984/version/1

- ↑ http://us.expasy.org/tools/

- ↑ http://www.es.embnet.org/Services/EMBnetAT/htdoc/9aatad/

- ↑ M. Uesugi and G. L. Verdine, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 (26), 14801 (1999); M. Uesugi, O. Nyanguile, H. Lu, A. J. Levine, and G. L. Verdine, Science 277 (5330), 1310 (1997); Y. Choi, S. Asada, and M. Uesugi, J Biol Chem 275 (21), 15912 (2000). C. W. Lee, M. Arai, M. A. Martinez-Yamout, H. J. Dyson, and P. E. Wright, Biochemistry (2009); N. K. Goto, T. Zor, M. Martinez-Yamout, H. J. Dyson, and P. E. Wright, J Biol Chem 277 (45), 43168 (2002); I. Radhakrishnan, G. C. Perez-Alvarado, D. Parker, H. J. Dyson, M. R. Montminy, and P. E. Wright, Cell 91 (6), 741 (1997); T. Zor, B. M. Mayr, H. J. Dyson, M. R. Montminy, and P. E. Wright, J Biol Chem 277 (44), 42241 (2002); S. Bruschweiler, P. Schanda, K. Kloiber, B. Brutscher, G. Kontaxis, R. Konrat, and M. Tollinger, Journal of the American Chemical Society (2009); G. H. Liu, J. Qu, and X. Shen, Biochimica et biophysica acta 1783 (5), 713 (2008); M. E. Massari, P. A. Grant, M. G. Pray-Grant, S. L. Berger, J. L. Workman, and C. Murre, Mol Cell 4 (1), 63 (1999); R. Bayly, T. Murase, B. D. Hyndman et al., Mol Cell Biol 26 (17), 6442 (2006); C. Garcia-Rodriguez and A. Rao, The Journal of experimental medicine 187 (12), 2031 (1998); S. Hong, S. H. Kim, M. A. Heo et al., FEBS letters 559 (1-3), 165 (2004); S. Mink, B. Haenig, and K. H. Klempnauer, Mol Cell Biol 17 (11), 6609 (1997); Martin Piskacek, Nature Precedings http://precedings.nature.com/documents/3488/version/2 (2009); Martin Piskacek, Nature Precedings http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/npre.2009.3939.1 (2009); S. Piskacek, M. Gregor, M. Nemethova, M. Grabner, P. Kovarik, and M. Piskacek, Genomics 89 (6), 756 (2007).

- ↑ Teufel DP, Freund SM, Bycroft M, Fersht AR (April 2007). "Four domains of p300 each bind tightly to a sequence spanning both transactivation subdomains of p53". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (17): 7009–14. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702010104. PMID 17438265.Teufel DP, Bycroft M, Fersht AR (May 2009). "Regulation by phosphorylation of the relative affinities of the N-terminal transactivation domains of p53 for p300 domains and Mdm2". Oncogene 28 (20): 2112–8. doi:10.1038/onc.2009.71. PMID 19363523.Feng H, Jenkins LM, Durell SR, Hayashi R, Mazur SJ, Cherry S, Tropea JE, Miller M, Wlodawer A, Appella E, Bai Y (February 2009). "Structural basis for p300 Taz2-p53 TAD1 binding and modulation by phosphorylation". Structure 17 (2): 202–10. doi:10.1016/j.str.2008.12.009. PMID 19217391.Ferreon JC, Lee CW, Arai M, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE (April 2009). "Cooperative regulation of p53 by modulation of ternary complex formation with CBP/p300 and HDM2". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (16): 6591–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811023106. PMID 19357310.Gamper AM, Roeder RG (April 2008). "Multivalent binding of p53 to the STAGA complex mediates coactivator recruitment after UV damage". Mol. Cell. Biol. 28 (8): 2517–27. doi:10.1128/MCB.01461-07. PMID 18250150.

- ↑ T. Fukasawa, M. Fukuma, K. Yano, and H. Sakurai, DNA Res 8 (1), 23 (2001); L. Badi and A. Barberis, Mol Genet Genomics 265 (6), 1076 (2001); Y. J. Kim, S. Bjorklund, Y. Li, M. H. Sayre, and R. D. Kornberg, Cell 77 (4), 599 (1994); Y. Suzuki, Y. Nogi, A. Abe, and T. Fukasawa, Mol Cell Biol 8 (11), 4991 (1988); J. S. Fassler and F. Winston, Mol Cell Biol 9 (12), 5602 (1989); J. M. Park, H. S. Kim, S. J. Han, M. S. Hwang, Y. C. Lee, and Y. J. Kim, Mol Cell Biol 20 (23), 8709 (2000); Z. Lu, A. Z. Ansari, X. Lu, A. Ogirala, and M. Ptashne, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 (13), 8591 (2002); M. J. Swanson, H. Qiu, L. Sumibcay et al., Mol Cell Biol 23 (8), 2800 (2003); G. O. Bryant and M. Ptashne, Mol Cell 11 (5), 1301 (2003); J. Fishburn, N. Mohibullah, and S. Hahn, Mol Cell 18 (3), 369 (2005); M. K. Lim, V. Tang, A. Le Saux, J. Schuller, C. Bongards, and N. Lehming, J Mol Biol 374 (1), 9 (2007); S. Lallet, H. Garreau, C. Garmendia-Torres, D. Szestakowska, E. Boy-Marcotte, S. Quevillon-Cheruel, and M. Jacquet, Molecular microbiology 62 (2), 438 (2006); M. Dietz, W. T. Heyken, J. Hoppen, S. Geburtig, and H. J. Schuller, Molecular microbiology 48 (4), 1119 (2003); T. Mizuno and S. Harashima, Mol Genet Genomics 269 (1), 68 (2003); J. K. Thakur, H. Arthanari, F. Yang et al., Nature 452 (7187), 604 (2008); J. K. Thakur, H. Arthanari, F. Yang, K. H. Chau, G. Wagner, and A. M. Naar, J Biol Chem 284 (7), 4422 (2009).

- ↑ J. Klein, M. Nolden, S. L. Sanders, J. Kirchner, P. A. Weil, and K. Melcher, J Biol Chem 278 (9), 6779 (2003).C. M. Drysdale, E. Duenas, B. M. Jackson, U. Reusser, G. H. Braus, and A. G. Hinnebusch, Mol Cell Biol 15 (3), 1220 (1995); E. Milgrom, R. W. West, Jr., C. Gao, and W. C. Shen, Genetics 171 (3), 959 (2005).

- ↑ Martin Piskacek, Nature Precedings http://precedings.nature.com/documents/3488/version/2 (2009); Martin Piskacek, Nature Precedings http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/npre.2009.3939.1 (2009); S. Piskacek, M. Gregor, M. Nemethova, M. Grabner, P. Kovarik, and M. Piskacek, Genomics 89 (6), 756 (2007).

- ↑ Littlewood TD, Evan GI (1995). "Transcription factors 2: helix-loop-helix". Protein profile 2 (6): 621–702. PMID 7553065.

- ↑ Vinson C, Myakishev M, Acharya A, Mir AA, Moll JR, Bonovich M (September 2002). "Classification of human B-ZIP proteins based on dimerization properties". Molecular and cellular biology 22 (18): 6321–35. doi:10.1128/MCB.22.18.6321-6335.2002. PMID 12192032.

- ↑ Wintjens R, Rooman M (September 1996). "Structural classification of HTH DNA-binding domains and protein-DNA interaction modes". Journal of molecular biology 262 (2): 294–313. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1996.0514. PMID 8831795.

- ↑ Gehring WJ, Affolter M, Bürglin T (1994). "Homeodomain proteins". Annual review of biochemistry 63: 487–526. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002415. PMID 7979246.

- ↑ Dahl E, Koseki H, Balling R (September 1997). "Pax genes and organogenesis". BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology 19 (9): 755–65. doi:10.1002/bies.950190905. PMID 9297966.

- ↑ Laity JH, Lee BM, Wright PE (February 2001). "Zinc finger proteins: new insights into structural and functional diversity". Current opinion in structural biology 11 (1): 39–46. doi:10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00167-6. PMID 11179890.

- ↑ Wolfe SA, Nekludova L, Pabo CO (2000). "DNA recognition by Cys2His2 zinc finger proteins". Annual review of biophysics and biomolecular structure 29: 183–212. doi:10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.183. PMID 10940247.

- ↑ Wang JC (March 2005). "Finding primary targets of transcriptional regulators". Cell Cycle 4 (3): 356–8. PMID 15711128. http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/abstract.php?id=1521.

- ↑ Semenza, Gregg L. (1999). Transcription factors and human disease. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511239-3.

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16475943 "Targeting transcription factors for cancer gene therapy." 2006

- ↑ Moretti P, Zoghbi HY (June 2006). "MeCP2 dysfunction in Rett syndrome and related disorders". Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 16 (3): 276–81. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2006.04.009. PMID 16647848.

- ↑ Chadwick LH, Wade PA (April 2007). "MeCP2 in Rett syndrome: transcriptional repressor or chromatin architectural protein?". Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 17 (2): 121–5. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2007.02.003. PMID 17317146.

- ↑ Maestro MA, Cardalda C, Boj SF, Luco RF, Servitja JM, Ferrer J (2007). "Distinct roles of HNF1beta, HNF1alpha, and HNF4alpha in regulating pancreas development, beta-cell function and growth". Endocr Dev 12: 33–45. doi:10.1159/0000109603 (inactive 2009-01-10). PMID 17923767.

- ↑ Al-Quobaili F, Montenarh M (April 2008). "Pancreatic duodenal homeobox factor-1 and diabetes mellitus type 2 (review)". Int. J. Mol. Med. 21 (4): 399–404. PMID 18360684. http://www.spandidos-publications.com/ijmm/article.jsp?article_id=ijmm_21_4_399.

- ↑ Lennon PA, Cooper ML, Peiffer DA, Gunderson KL, Patel A, Peters S, Cheung SW, Bacino CA (April 2007). "Deletion of 7q31.1 supports involvement of FOXP2 in language impairment: clinical report and review". Am. J. Med. Genet. A 143A (8): 791–8. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.31632. PMID 17330859.

- ↑ van der Vliet HJ, Nieuwenhuis EE (2007). "IPEX as a result of mutations in FOXP3". Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2007: 89017. doi:10.1155/2007/89017. PMID 18317533.

- ↑ Iwakuma T, Lozano G, Flores ER (July 2005). "Li-Fraumeni syndrome: a p53 family affair". Cell Cycle 4 (7): 865–7. PMID 15917654. http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/abstract.php?id=1800.

- ↑ http://ajp.amjpathol.org/cgi/content/full/165/5/1449 "Roles and Regulation of Stat Family Transcription Factors in Human Breast Cancer" 2004

- ↑ http://www.ias.surrey.ac.uk/reports/hox-report.html "Transcription factors as targets and markers in cancer" Workshop 2007

- ↑ Overington JP, Al-Lazikani B, Hopkins AL (2006). "How many drug targets are there?". Nature reviews. Drug discovery 5 (12): 993–6. doi:10.1038/nrd2199. PMID 17139284.

- ↑ Gronemeyer H, Gustafsson JA, Laudet V (November 2004). "Principles for modulation of the nuclear receptor superfamily". Nat Rev Drug Discov 3 (11): 950–64. doi:10.1038/nrd1551. PMID 15520817.

- ↑ Bustin SA, McKay IA (June 1994). "Transcription factors: targets for new designer drugs". Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 51 (2): 147–57. PMID 8049612.

- ↑ Butt TR, Karathanasis SK (1995). "Transcription factors as drug targets: opportunities for therapeutic selectivity". Gene Expr. 4 (6): 319–36. PMID 7549464.

- ↑ Papavassiliou AG (August 1998). "Transcription-factor-modulating agents: precision and selectivity in drug design". Mol Med Today 4 (8): 358–66. PMID 9755455.

- ↑ Ghosh D, Papavassiliou AG (2005). "Transcription factor therapeutics: long-shot or lodestone". Curr. Med. Chem. 12 (6): 691–701. PMID 15790306. http://www.bentham-direct.org/pages/content.php?CMC/2005/00000012/00000006/0005C.SGM.

- ↑ Moellering RE, Cornejo M, Davis TN, Del Bianco C, Aster JC, Blacklow SC, Kung AL, Gilliland DG, Verdine GL, Bradner JE (November 2009). "Direct inhibition of the NOTCH transcription factor complex". Nature 462 (7270): 182–8. doi:10.1038/nature08543. PMID 19907488. Lay summary – The Scientist.

- ↑ EntrezGene database [1]

- ↑ Wenta N, Strauss H, Meyer S, Vinkemeier U (2008). "Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates the partitioning of STAT1 between different dimer conformations". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 (27): 9238–43. PMID 18591661.

- ↑ Sermeus A, Cosse JP, Crespin M, Mainfroid V, de Longueville F, Ninane N, Raes M, Remacle J, Michiels C (2008). "Hypoxia induces protection against etoposide-induced apoptosis: molecular profiling of changes in gene expression and transcription factor activity". Mol Cancer 7: 27. PMID 18366759.

- ↑ Orphanides G, Lagrange T, Reinberg D (1996). "The general transcription factors of RNA polymerase II". Genes Dev. 10 (21): 2657–83. doi:10.1101/gad.10.21.2657. PMID 8946909.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Walter F., PhD. Boron (2003). Medical Physiology: A Cellular And Molecular Approaoch. Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 125–126. ISBN 1-4160-2328-3.

- ↑ Stegmaier P, Kel AE, Wingender E (2004). "Systematic DNA-binding domain classification of transcription factors". Genome informatics. International Conference on Genome Informatics 15 (2): 276–86. PMID 15706513. http://www.jsbi.org/journal/GIW04/GIW04F028.html.

- ↑ Matys V, Kel-Margoulis OV, Fricke E, Liebich I, Land S, Barre-Dirrie A, Reuter I, Chekmenev D, Krull M, Hornischer K, Voss N, Stegmaier P, Lewicki-Potapov B, Saxel H, Kel AE, Wingender E (2006). "TRANSFAC and its module TRANSCompel: transcriptional gene regulation in eukaryotes". Nucleic Acids Res. 34 (Database issue): D108–10. doi:10.1093/nar/gkj143. PMID 16381825.

- ↑ "TRANSFAC database". http://www.gene-regulation.com/pub/databases/transfac/cl.html. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

External links

- MeSH Transcription+Factors

- "DBD: Transcription factor database Home". http://transcriptionfactor.org/. Retrieved 2008-03-02.[1]

- Gilbert FS. "Transcription factors: DevBio on-line supplementary material to Developmental Biology". Sinauer Associates. http://8e.devbio.com/article.php?ch=5&id=39. Retrieved 2008-03-02.[2]

- "Transcription Factor Classification, A classification of transcription factors based on their DNA-binding domains". BIOBASE GmbH. 2002-10-01. http://www.gene-regulation.com/pub/databases/transfac/cl.html. Retrieved 2008-03-02.[3]

- "Image of transcription factor function in humans". Access Excellence, The National Health Museum. http://www.accessexcellence.org/RC/VL/GG/ecb/ecb_images/08_10_transcription_factors.jpg. Retrieved 2008-03-02. Figure 8-10 from Essential cell biology.[4]

Further reading

- ↑ Wilson D, Charoensawan V, Kummerfeld SK, Teichmann SA (2008). "DBD--taxonomically broad transcription factor predictions: new content and functionality". Nucleic Acids Res. 36 (Database issue): D88–92. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm964. PMID 18073188.

- ↑ Singer, Susan R.; Gilbert, Scott F. (2006). Developmental Biology. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-250-X.

- ↑ Matys V, Kel-Margoulis OV, Fricke E, Liebich I, Land S, Barre-Dirrie A, Reuter I, Chekmenev D, Krull M, Hornischer K, Voss N, Stegmaier P, Lewicki-Potapov B, Saxel H, Kel AE, Wingender E (2006). "TRANSFAC and its module TRANSCompel: transcriptional gene regulation in eukaryotes". Nucleic Acids Res. 34 (Database issue): D108–10. doi:10.1093/nar/gkj143. PMID 16381825.

- ↑ Bruce Alberts, Dennis Bray, Karen Hopkin, Alexander Johnson, Julian Lewis, Martin Raff, Keith Roberts, Peter Walter (2004). Essential cell biology. New York: Garland Science. pp. 896 pages. ISBN 0-8153-3480-X.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||